These comments are addressed to Chapter Two, sub-head: "The Lawlessness of the Dying Trumpeter - and of Paul" (pp. 78-82).

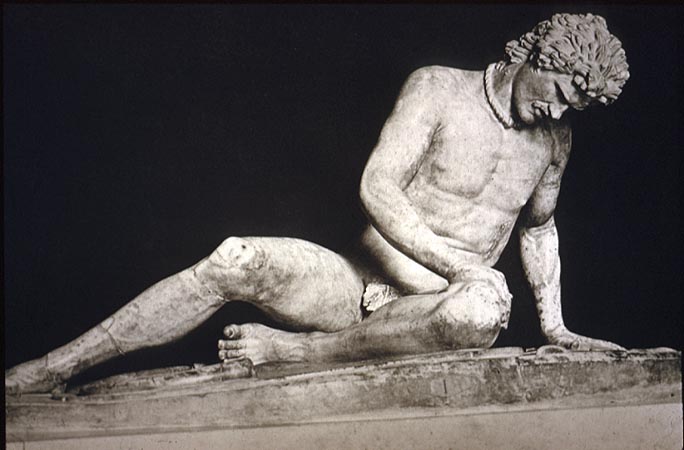

Kahl asserts, that the image of the Dying Trumpeter / Dying Gaul was ubiquitous across the Greek and Roman worlds ("omnipresent images" page 79) and in the first century was understood by means of "a common sigh system of otherness" (p. 78) which "Paul and the Galatians of his letter would "have no difficulty reading" (p. 79).

These assertions lead Kahl to further argue that this sculpture informs not simply the context of Paul's Galatians letter, but the argument(s) contained in the letter. This is so, Kahl states, because of two features of the sculpture: (1) the presentation of an uncircumcised penis and (2) the assailant who has delivered the lethal blow is not pictured.

Conflating the centuries older sculpture with the contemporaneous Galatians of Paul's letter, Kahl allows the imagery of the art to represent the circumstance of Galatians, per se, whose ancestors had been defeated in war. The analogy seems to run in the opposite chronological direction as well: "Is there any relation between his [the statue's] foreskin and the mortal would on his side? And who inflicted the wound? [. . .] Is it Jewish law that has cruelly punished the dying man for not complying with the 'works' of circumcision?"

Kahl expects her reader to see such questions as "bizarre" because, in her view, the tension about circumcision has little or nothing to do with Torah and much to do with the imperious law of the Roman occupiers.

As mentioned in an earlier post, the photographic image below is taken from William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (London: John Murry, 1875) see pp. 574-77.

This sculpture, taken as representing Paul's Galatian converts, means to Kahl (p. 80), "it is not Jewish particularism or ethnocentrism that has struck him [i.e. the Dying Gaul] down but Cesar's imperial universalism."

Are we to impute imperial Roman pretensions to Greek sculpture of an earlier date simply because Rome took possession of these objects?

Even if this question is answered affirmatively, where is there an association between the sculpture and the letter dictated by the Apostle Paul?

One of the problems Kahl faces is that of assigning significance to a work of art, on behalf of an absent set of supposed viewers.

Art engages with individual sensibilities and perceptions which inform each viewer's understanding. Is there a 'correct' way to understand a work of art? Can a particular understanding of a sculpture be assigned with confidence to observers in another time and place?

Art engages with individual sensibilities and perceptions which inform each viewer's understanding. Is there a 'correct' way to understand a work of art? Can a particular understanding of a sculpture be assigned with confidence to observers in another time and place?

A specific historical problem is that much art from the Greek and later Roman eras display an uncircumcised penis. On what grounds is one entitled to announce that any one of these works of art is part of an argument about circumcision?

As mentioned in an earlier post, the surviving marble sculpture of the Dying Gaul / Dying Trumpeter appears, to me, to have been modeled on an even older, strikingly similar bronze figure from the sanctuary of Aphaia, at Aegina, a depiction of Trojan King Laomedon, killed by an arrow from Herakles (Heracles), during the first campaign against Troy. (This image may be found in A History of Ancient Sculpture, Vol 2, by Lucy Mitchell (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1883) p. 244.)

This image also displays a penis. Are we to speculate then that this image, too. is a critique of circumcision? On what grounds, whether historical, esthetic or literary, can this association be made?

In this image, as with the Dying Gaul, the attacker is absent. Dos this mean we are entitled to declare that the attacker is Roman, since imperial Rome later came into possession of Greek art?

Professor Kahl concludes (p. 81) this section by citing an ambiguous comment from Paul (Gal 6:11-13) wherein Paul seems to be saying that those who insist the Galatians must be circumcised, do so "that they may not be persecuted."

Kahl implies that Paul is here referring to "a third party" which Kahl, herself writing ambiguously, takes as "something or someone," of whom Paul's circumcision-insisting adversaries "are genuinely afraid."

Whether a single one of Paul's Galatians ever viewed this sculpture on a single occasion is simply asserted to be true; they all must have seen this statue because it was "omnipresent."

This assertion permits Kahl to speculate that Paul's adversaries might be afraid of the same "invisible hand that struck the deadly blow against the Trumpeter."

This further assertion muddies what is known of the provenance of the sculpture of the Dying Gaul, representing as it does, an adversary defeated in a Greek or Pergamene victory, not a Roman one.

For a new interpretative key to be accepted, displacing a former understanding, the new idea cannot be merely plausible. The new approach must be more plausible than the older approaches. We are not at this point, so far in Kahl's presentation.

In this image, as with the Dying Gaul, the attacker is absent. Dos this mean we are entitled to declare that the attacker is Roman, since imperial Rome later came into possession of Greek art?

Professor Kahl concludes (p. 81) this section by citing an ambiguous comment from Paul (Gal 6:11-13) wherein Paul seems to be saying that those who insist the Galatians must be circumcised, do so "that they may not be persecuted."

Kahl implies that Paul is here referring to "a third party" which Kahl, herself writing ambiguously, takes as "something or someone," of whom Paul's circumcision-insisting adversaries "are genuinely afraid."

Whether a single one of Paul's Galatians ever viewed this sculpture on a single occasion is simply asserted to be true; they all must have seen this statue because it was "omnipresent."

This assertion permits Kahl to speculate that Paul's adversaries might be afraid of the same "invisible hand that struck the deadly blow against the Trumpeter."

This further assertion muddies what is known of the provenance of the sculpture of the Dying Gaul, representing as it does, an adversary defeated in a Greek or Pergamene victory, not a Roman one.

For a new interpretative key to be accepted, displacing a former understanding, the new idea cannot be merely plausible. The new approach must be more plausible than the older approaches. We are not at this point, so far in Kahl's presentation.

No comments:

Post a Comment