Professor Kahl's brief Conclusion (pp. 287-89) summarizes what Kahl asserts has been demonstrated in this investigation.

Kahl believes (p. 287) that she has shown that "the entire letter is a 'coded' theological manifesto of the nations of the world pledging allegiance to the one God who is other than Caesar . . ."

Is this description of the intent of the writer of the Galatians letter meant by Kahl to be taken ironically?

A manifesto is a public announcement of principles or intentions. A cryptic statement cannot be described as a manifesto because the intended meaning of a cryptic message is something other than what is stated in the literal message. This is the opposite of manifest-o.

The coded-manifesto conundrum is twinned with that other conundrum, already commented upon, wherein what the Galatians letter may be taken to mean by subsequent, unintended readers is retrojected upon the mental processes of the writer as his personal, intended meaning given by him to his own words.

For some readers, the Galatians letter may become "a passionate plea to resist the idolatrous lure of imperial religion and social ordering" (Kahl at p. 287). But evidence is lacking that Paul meant for such a coded message to be read into his statements by readers he addressed in Galatia.

What is up with Galatians?

Paul is confronting sharp criticisms of his own authority and message, raised by Jewish messianists, who were victims of his brutal treatment of them when he operated as an enforcer of temple and synagogue mores. (See my article, “Paul and the Victims of His Persecution: The Opponents in Galatia” 32 Biblical Theology Bulletin No 4 (Winter 2002) pages 182-191.)

Paul's over-heated response to his critics in Galatia is to denounce to his wavering converts his victims' description of himself. He insists he is not a transgressor of Torah who represents no one. After making these denials, Paul launches into a reassertion of his theological claims, which had earlier impressed the Galatian converts.

By this gambit, Paul is changing the subject. He dismisses his critics and devotes the balance of his dictation to a reprise of his complicated rearrangement of Jewish religious history, which elevates Abraham at the expense of Moses and invites gentiles into allegiance to a Jewish messiah by denigration of the rituals propounded by Torah, because Torah is limited chronologically, ending with the advent of Messiah Jesus.

It may be true, as Kahl concludes (p. 288), that Paul did not see himself as "breaking away from Judaism." But in fact, by demeaning Moses and denying the validity of Torah observance, this is what he did.

One further irony. In a book which expressly declares the "commonality" of all, we are told in the last sentence of the Conclusion, that "only" by seeing things as Paul prescribed, do we see things aright.

"Philosophy is like trying to open a safe with a combination lock: each little adjustment of the dials seems to achieve nothing, only when everything is in place does the door open." Ludwig Wittgenstein

Showing posts with label Paul. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Paul. Show all posts

Friday, June 10, 2011

RESPONSE NUMBER FORTY-THREE To Galatians Re-imagined: Reading with the Eyes of the Vanquished (Fortress 2010) by Brigitte Kahl

Labels:

Biblical Theology Bulletin,

Caesar,

Gager,

Galatians,

Gaston,

Krister Stendahl,

Paul,

Professor Kahl

Saturday, May 14, 2011

RESPONSE NUMBER FORTY To Galatians Re-imagined: Reading with the Eyes of the Vanquished (Fortress 2010) by Brigitte Kahl

This post is prompted by endnote 91 in Chapter 6 (p. 367).

Professor Kahl, amplifying (p. 283) her comments about Gal 3:19-20, offers a unique reading of this text, which amounts to a concise summary of the thesis of her book.

Kahl is commenting on the phrase henos ouk estin (Gal 3:20)

“But a mediator is not one (lit: ‘not of the one’), but God is one.”

Kahl writes that “this most cryptic statement . . . is a coded reference to Caesar.”

Elaborating further, Kahl finds that Paul, “in guarded language . . . evokes the core conflict of the entire letter as the idolatrous claim of the Roman emperor as the supreme guardian and grantor of law vis-a-vis subject nations, including Jewish law, and the enslaving powers unleashed through his false promises and decrees of ‘law mediation.’

Is it plausible that Paul is referring explicitly, though cryptically, to Caesar? I suppose, once the view is taken that a comment is deliberately "cryptic" then it follows that a comment can mean anything.

But the plausibility of a particularly novel suggestion comes always into play. Kahl in this footnote reads Gal 3:20 in light of Gal 1:1 - Paul’s assertion that his Gospel is “not from men nor through a man” - which Kahl suggests is “a puzzling reference” and which may also point to Caesar.

In Gal 1:1 the emphatic, repetative negative (not from . . . nor through) does not suggest this is to be taken as a cryptic comment. More likely, Paul is asserting a divine source for his missionary authority, while denying a human source - as may have been alleged of him by critics in Galatia. If so, Paul does not have in mind the Roman emperor or any other particular individual and his dictated comment more likely means not from mankind or not from any human source.

My conclusion is that neither Gal 1:1 nor 3:20 should be taken as a reference to Caesar.

In this case Professor Kahl’s proposal is not sustained. Caesar is not characterized in Galatians as a false god, who is countered by Paul, who asserts belief in what he insists is the only true God, who made direct promises to Abraham, conducted arm's length dealings with Moses and is father of Messiah Jesus.

It follows that, if Caesar is not in view in Galatians, then nomos (law) in the Galatians letter is not to be taken as a reference to Roman law (however defined) and that the phrase “works of the law” ought to be read, not as the obligations of subject people to worship Caesar, but rather as a reference to Torah observance.

Labels:

Emperor,

Gal 1:1,

Gal 3:20,

Jewish law,

Paul,

Professor Kahl,

Roman law,

Torah

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

RESPONSE NUMBER THIRTY-EIGHT To Galatians Re-imagined: Reading with the Eyes of the Vanquished (Fortress 2010) by Brigitte Kahl

Continuing our consideration of Professor Kahl's explication of portions of Galatians 2 (pp. 279-81), this reader is struck by the forced and, unfortunately, contrived conclusions reached.

In the previous post, I commented on Kahl's treatment of Cephas' reversal of policy as to eating with Gentiles.

At first, he is down with it, then he withdraws. But Kahl does not acknowledge his earlier willingness to eat in a non-kosher manner. Instead, Kahl interprets his withdrawal as ( p. 279) "enforced 'judaizing' of the Gentiles (ioudazein, 2:14) as in fact a gesture of civic/imperial conformism."

Professor Kahl wants to use this incident in support of the theory that the failure to keep kosher would somehow endanger the observant Jewish community in Antioch, and presumably in Jerusalem.

But if attention is drawn to Cephas' earlier practice of eating with Gentiles, where is the fear of the Romans?

The incident tells us that Cephas withdrew from table fellowship upon the arrival of observant Jews, not because of a fear of the occupying power.

I suppose one might argue that if I refuse to eat with you, I am forcing you to follow my cleanliness rules, but this is strained. Cephas, after at first ignoring Jewish cleanliness rules, changed direction when observant, messianic Jews arrived from Jerusalem; their arrival caused Cephas to revert to kosher practice.

By this reversal, Cephas was breaking fellowship with Christian Gentiles; he was not insisting that they themselves follow kosher dietary rules, out of fear of the Roman occupation.

In a similarly forced reading of Gal 2:14, Kahl has Paul (p. 280) express condemnation "not of a Jewish apostasy but of an idolatrous apostasy towards a non-Jewish imperial way of life that he calls ethnikos." Thus, Kahl wants her readers to see Paul expressing antipathy towards subservience to Roman rule, as manifested by Cephas' insistence that Gentiles adopt Jewish ways - in conformity not with Torah observance but with world nomos.

World nomos. World rule. The law of the Romans. Can this be what Paul is talking about in Gal 2:14 and following?

Professor thinks so and reads Gal 2:15-21 and its reference to "Works of the law" as Paul entering upon a discussion not of Torah observance but of "works of self-righteousness and vertical distinction between self and other."

This comment and subsequent ones (p. 281) may be acceptable as homiletical applications of 2:15-21, but this is not a delineation of what Paul actually says.

The text:

My translation:

15: But we, being Jews and not wicked Gentiles,

16: Know that no one is found acceptable by observance of the law ("works of the law") but rather by the faith of Jesus Messiah, and we trust in Messiah Jesus, that we might be accepted by the faith of Jesus and not by observance of the law, by which no one is found acceptable.

17: But! In seeking acceptance by way of Messiah, do we find him wicked? Or a servant of wickedness? Of course not!

18: Now if I rebuild what has been demolished even I would consider myself a transgressor!

19: For I, through operation of Torah have died to Torah - so I might live to God.

20: I longer live. Messiah lives through me! Yet I live on in the flesh, I live in confidence in the son of God, who loved me and gave himself up for me!

21: I shall not denigrate God's goodwill. If acceptance is through observances, then Messiah died for nothing!

Paul is here engaged in a dialogue with Torah, that is, with his own former allegiance to God through the keeping of Torah. Although every reference to nomos - law in Galatians is not a reference to Torah, this is the meaning of nomos in these verses.

"Wicked Gentiles" (v 15) should be taken hyperbolically and perhaps sarcastically. To heighten the contrast between the Torah observance and non-Jewish uncleanliness, Paul may be saying filthy Gentiles.

Paul's assertion (v. 17) that "no one" finds acceptance before God by way of Torah is a statement no observant Jew could accept. Here, Paul has clearly placed himself outside traditional Judaism or even sectarian Judaism, since he is denigrating the very purpose of Torah.

Having positioned himself outside Judaism, he looks at this from the inside (v. 18) and acknowledges: if I were to re-enter the edifice of Torah observance, I would certainly see my former behavior (allegiance to a criminally executed Messiah) as a transgression against Torah.

In v. 19, he steps back outside the old edifice to assert that his new status, life in God, has come about by virtue of his having abandoned Torah once and for all.

"I no longer live" (v. 20) ius yet another assertion of Paul's view that his former Torah observance way of life is "dead," having been replaced by his living confidence in the willing death of Messiah Jesus, who was a sacrifice for himself.

Verse 21 is shorthand; Paul way of summarizing the grand design (as he has worked it out) and asserting, 'Having worked out what God designed, which was that the futility of Torah observance would be demonstrated by the execution of the Messiah, I will not dismiss this design, since to do so would be to assert that it was for nothing that God permitted Messiah to be executed.'

While I have misgivings about the edifice that has been erected on the rubble Paul declared to be Torah observance, there is no doubt that Paul is here talking about Torah, when he speaks of law.

Professor Kahl sees matters differently.

Professor Kahl has Paul, voluntarily and for all important purposes, still on the Jewish side of the Jew-Gentile equation. She see Paul maintaining a double Gospel approach, one to Jews, one to Gentiles, over against Gentile world law, expressed through the Roman occupation.

Kahl sees Paul expressing hostility towards those who bend the knee to Rome, by practicing a Judaism of civil conformism to the purposes of empire.

It is this Judaism, which Paul condemns in Antioch and which Kahl suggests can, in an albeit convoluted way, as a sort of puppet of the all-controlling Gentile (Roman) way, condemns Paul as a "transgressor" (2:18).

But this very labored result - an observant Judaism of civil conformity - hangs together only by reshaping the Antioch narrative (Gal 11-14) to make it about coercion of messianic Gentiles, out of fear of local Roman authority. These themes are absent from the narrative, as Paul laid it out.

In the previous post, I commented on Kahl's treatment of Cephas' reversal of policy as to eating with Gentiles.

At first, he is down with it, then he withdraws. But Kahl does not acknowledge his earlier willingness to eat in a non-kosher manner. Instead, Kahl interprets his withdrawal as ( p. 279) "enforced 'judaizing' of the Gentiles (ioudazein, 2:14) as in fact a gesture of civic/imperial conformism."

Professor Kahl wants to use this incident in support of the theory that the failure to keep kosher would somehow endanger the observant Jewish community in Antioch, and presumably in Jerusalem.

But if attention is drawn to Cephas' earlier practice of eating with Gentiles, where is the fear of the Romans?

The incident tells us that Cephas withdrew from table fellowship upon the arrival of observant Jews, not because of a fear of the occupying power.

I suppose one might argue that if I refuse to eat with you, I am forcing you to follow my cleanliness rules, but this is strained. Cephas, after at first ignoring Jewish cleanliness rules, changed direction when observant, messianic Jews arrived from Jerusalem; their arrival caused Cephas to revert to kosher practice.

By this reversal, Cephas was breaking fellowship with Christian Gentiles; he was not insisting that they themselves follow kosher dietary rules, out of fear of the Roman occupation.

In a similarly forced reading of Gal 2:14, Kahl has Paul (p. 280) express condemnation "not of a Jewish apostasy but of an idolatrous apostasy towards a non-Jewish imperial way of life that he calls ethnikos." Thus, Kahl wants her readers to see Paul expressing antipathy towards subservience to Roman rule, as manifested by Cephas' insistence that Gentiles adopt Jewish ways - in conformity not with Torah observance but with world nomos.

World nomos. World rule. The law of the Romans. Can this be what Paul is talking about in Gal 2:14 and following?

Professor thinks so and reads Gal 2:15-21 and its reference to "Works of the law" as Paul entering upon a discussion not of Torah observance but of "works of self-righteousness and vertical distinction between self and other."

This comment and subsequent ones (p. 281) may be acceptable as homiletical applications of 2:15-21, but this is not a delineation of what Paul actually says.

The text:

My translation:

15: But we, being Jews and not wicked Gentiles,

16: Know that no one is found acceptable by observance of the law ("works of the law") but rather by the faith of Jesus Messiah, and we trust in Messiah Jesus, that we might be accepted by the faith of Jesus and not by observance of the law, by which no one is found acceptable.

17: But! In seeking acceptance by way of Messiah, do we find him wicked? Or a servant of wickedness? Of course not!

18: Now if I rebuild what has been demolished even I would consider myself a transgressor!

19: For I, through operation of Torah have died to Torah - so I might live to God.

20: I longer live. Messiah lives through me! Yet I live on in the flesh, I live in confidence in the son of God, who loved me and gave himself up for me!

21: I shall not denigrate God's goodwill. If acceptance is through observances, then Messiah died for nothing!

Paul is here engaged in a dialogue with Torah, that is, with his own former allegiance to God through the keeping of Torah. Although every reference to nomos - law in Galatians is not a reference to Torah, this is the meaning of nomos in these verses.

"Wicked Gentiles" (v 15) should be taken hyperbolically and perhaps sarcastically. To heighten the contrast between the Torah observance and non-Jewish uncleanliness, Paul may be saying filthy Gentiles.

Paul's assertion (v. 17) that "no one" finds acceptance before God by way of Torah is a statement no observant Jew could accept. Here, Paul has clearly placed himself outside traditional Judaism or even sectarian Judaism, since he is denigrating the very purpose of Torah.

Having positioned himself outside Judaism, he looks at this from the inside (v. 18) and acknowledges: if I were to re-enter the edifice of Torah observance, I would certainly see my former behavior (allegiance to a criminally executed Messiah) as a transgression against Torah.

In v. 19, he steps back outside the old edifice to assert that his new status, life in God, has come about by virtue of his having abandoned Torah once and for all.

"I no longer live" (v. 20) ius yet another assertion of Paul's view that his former Torah observance way of life is "dead," having been replaced by his living confidence in the willing death of Messiah Jesus, who was a sacrifice for himself.

Verse 21 is shorthand; Paul way of summarizing the grand design (as he has worked it out) and asserting, 'Having worked out what God designed, which was that the futility of Torah observance would be demonstrated by the execution of the Messiah, I will not dismiss this design, since to do so would be to assert that it was for nothing that God permitted Messiah to be executed.'

While I have misgivings about the edifice that has been erected on the rubble Paul declared to be Torah observance, there is no doubt that Paul is here talking about Torah, when he speaks of law.

Professor Kahl sees matters differently.

Professor Kahl has Paul, voluntarily and for all important purposes, still on the Jewish side of the Jew-Gentile equation. She see Paul maintaining a double Gospel approach, one to Jews, one to Gentiles, over against Gentile world law, expressed through the Roman occupation.

Kahl sees Paul expressing hostility towards those who bend the knee to Rome, by practicing a Judaism of civil conformism to the purposes of empire.

It is this Judaism, which Paul condemns in Antioch and which Kahl suggests can, in an albeit convoluted way, as a sort of puppet of the all-controlling Gentile (Roman) way, condemns Paul as a "transgressor" (2:18).

But this very labored result - an observant Judaism of civil conformity - hangs together only by reshaping the Antioch narrative (Gal 11-14) to make it about coercion of messianic Gentiles, out of fear of local Roman authority. These themes are absent from the narrative, as Paul laid it out.

Labels:

Antioch,

Nomos,

Paul,

Professor Kahl,

Torah,

Works of the Law

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

RESPONSE NUMBER THIRTY-SIX To Galatians Re-imagined: Reading with the Eyes of the Vanquished (Fortress 2010) by Brigitte Kahl

Further along in Chapter Six, one finds a fuller engagement by Brigitte Kahl, with some of Paul's statements taken from the text of the Galatains letter. This engagement is welcome but problematic.

A discussion of only selected statements falls well short of detailed exegesis. The lack of this kind of investigation is a disappointment in a book, which wants to see Paul in Galatians mounting a critical (yet cryptic) argument against the public worship of the emperor.

Professor Kahl’s treatment of Gal 6:4 (p. 271) may serve as an example.

Professor Kahl’s treatment of Gal 6:4 (p. 271) may serve as an example.

My translation:

“Each person should assess one’s own work and so take pride in (eis) one’s own alone and not in (eis) that of another.”

Kahl translates differently,

“Everybody should evaluate the work of himself or herself and then will have the boast in front of (eis) himself or herself alone.”

By way of this awkward translation, Kahl utilizes this statement to assert (see quotation below) that Paul, sarcastically, is arguing against public display, that is against the public show of allegiance to the emperor.

To enlist Paul’s sentence in the service of an argument against a display of public allegiance to the emperor, Kahl deploys the preposition eis, in translation to mean, “in front of.” By way of this translation, Paul can be said to have public acts ("works") in mind, which he then, sarcastically, dismisses: display yourself privately, not in front of anyone else.

But the issue in this statement is not display but judging. Kahl substitutes display for judging by combining the two appearances of the preposition, eis.

The preposition eis entails a range of meanings depending on its context (see Gal 3:17 and 4:11).

But this preposition cannot be said to mean “in front of” to the exclusion of the notion that Paul is calling on his readers to make, individually, an internal or private assessment of one’s own conduct.

In Gal 6:4 Paul clearly admonishes his readers not to assess the conduct of others. Kahl does not allow this meaning to be given to this verse.

Why not?

Kahl wishes to use Gal 6:4 to characterize Paul as mounting an “up-front attack on the competitive system of euergetism/benefactions, which, as we have seen, is a key feature of imperial order in a province like Galatia, ‘works’ are declared to be no longer the showcase of the self in the public race for status.”

To make Gal 6:4 carry all of this weight, Kahl declares that chapters 5 and 6 of Galatians have been dismissed by many of the commentators, who find earlier sections of the letter to be more substantive.

But in fact, the very statement Kahl enlists here, Gal 6:4, is best understood as Paul’s invocation of a general counsel to right conduct.

NOTE: The Greek text of Gal 6:4 has been taken from:

Labels:

Brigitte Kahl,

Gal:6:4,

Galatians,

Paul

Tuesday, April 5, 2011

RESPONSE NUMBER THIRTY-FOUR To Galatians Re-imagined: Reading with the Eyes of the Vanquished (Fortress 2010) by Brigitte Kahl

Brigitte Kahl, in Chapter Six, endeavors to tie all the rhetorical threads tightly together, and so demonstrate the cogency of the re-imagination of Galatians, which has been the driving impulse of this book.

Added here (p. 245 f.) is an illuminating series of comments on the first nine verses of Galatians, chapter one.

Kahl's juxtaposition of Paul's amen and anathema is striking.

These terms operate exactly as Kahl states (p. 247); they "impose themselves at the outset of Paul's letter and at the onset of occidental Pauline interpretation as well." Again (p. 248): "If Jewishness is anathema the countervailing amen must affirm Christianity. This reading produced the birth of the Christian self, out of, and in anthesis to the Jewish other . . ."

This doctrinal development is a source of regret, and not only to Brigitte Kahl, but to many who see and lament an ethnocentric resonance down the centuries, which vindicates itself in Paul's angry condemnation of those of his own day, who display a narrowness even more constricted than his own.

Kahl would rehabilitate Paul but at the expense of the essential logic of his response to his circumstances.

It is an overreach to assert (p. 258) that "Paul's Amen and Anathema echo from the Great Frieze" of the Pergamon altar.

Kahl would re-imagine a different circumstance, one in which Paul is not contesting the exclusionary praxis of Judaism but rather is contending with Augustus himself.

Kahl (p. 247) would have Paul's rhetoric placing us, his late readers, "right back at the foot of the great alar in Pergamon" where she believes, all of his readers are directed by Paul's own deepest concerns - resistance to the empire of the caesars.

Kahl's explication of an "intertextual retelling" (p. 251) helpfully opens Paul's text to creative re-application as anti-imperial in its essence. This is a homiletical gambit.

Kahl and the scholars Kahl cites with approval, as experts in 'intertextual' matters, delineate the indices of the 'intertextual' markers which, coincidentally, have been found in the material they wish to see as relevant. This is like cutting out puzzle pieces and then announcing that one has been successful in putting a puzzle together.

As I have suggested in earlier comments , the context of the material found in Paul's Galatians letter is not illuminated by the linkage Kahl finds between the text of this very specifically focused letter and representational art found at Pergamon.

The constant harkening back to visual art, fashioned decades if not centuries earlier, is warranted neither by what can be surmised from Roman republican and imperial history nor from the circumstances of Paul and his messianic converts in Galatia.

Nor is it illuminating to suggest that what can be called "cryptic" in Galatians is best understood (p. 252) as "a semi-hidden (or semi-public) transcript circulating among the dominated that has an anti-Roman core message."

This is all too forced. Here is an example:

The "single man" of Gal 1:1 is not the emperor in Rome, and so, is not a clue to Paul's intended readers, that "the whole of the following letter needs to be read in an anti-imperial key" (page 257).

Gal 1:1

contains the phrase, 'nor through (a) man' which Kahl takes as a reference to Caesar and from this, concludes (p. 257), that "the law and religion that Paul primarily criticizes are the law and religion not of Judaism but of the Roman empire."

But a perfectly acceptable translation of the verse and therefore of Kahl's cornerstone phrase is:

Paul, an emissary, neither through men nor by a man, but through Messiah Jesus and Father God, who raised him from the dead

Kahl takes "a man" as a cryptic reference to a specific individual, Caesar. This conclusion is stated without addressing a more likely reading.

Paul is asserting that his credentials as a missionary-organizer have been conferred upon him by God. Paul is contradicting his critics, who have asserted that Paul is lacking in qualification and/or proper appointment.

This being the case the reading that suggests itself is that Paul means to contrast positively, his assertion of his own divine commission with a commission or credential dependent, negatively, merely upon human agency. It is not likely that Paul has a specific person in mind.

Even if a specific person is referenced here, as some commentators suggest - someone whom Paul intends to denigrate - the reference is to a leader of the messianists in either Antioch or in Jerusalem.

The human-agency conclusion has been reached by many; ("human channel" Burton, p. 3 [1968]; 'human in origin" Betz, p. 39; "not depend on human authorization" Dunn, p. 26; anthropos = "the human orb" Martyn, p. 84).

Kahl, in proposing an entirely new interpretative direction, i.e., that Paul is here referring however cryptically to Caesar, ought first contend with comments which point, cogently, in another direction - not through any human being.

In sum, Professor Kahl, in chapter six, is engaged in homiletical gambits, not historical investigations.

That's OK with me. "It's right to praise . . . not meaning, but feeling . . . " ("Why I'm Here" by Jacqueline Berger, from The Gift That Arrives Broken. © Autumn House Press, 2010.)

NOTE: The Greek text of Gal 1:1, used above, has been taken from Greek New Testament

Added here (p. 245 f.) is an illuminating series of comments on the first nine verses of Galatians, chapter one.

Kahl's juxtaposition of Paul's amen and anathema is striking.

These terms operate exactly as Kahl states (p. 247); they "impose themselves at the outset of Paul's letter and at the onset of occidental Pauline interpretation as well." Again (p. 248): "If Jewishness is anathema the countervailing amen must affirm Christianity. This reading produced the birth of the Christian self, out of, and in anthesis to the Jewish other . . ."

This doctrinal development is a source of regret, and not only to Brigitte Kahl, but to many who see and lament an ethnocentric resonance down the centuries, which vindicates itself in Paul's angry condemnation of those of his own day, who display a narrowness even more constricted than his own.

Kahl would rehabilitate Paul but at the expense of the essential logic of his response to his circumstances.

It is an overreach to assert (p. 258) that "Paul's Amen and Anathema echo from the Great Frieze" of the Pergamon altar.

Kahl would re-imagine a different circumstance, one in which Paul is not contesting the exclusionary praxis of Judaism but rather is contending with Augustus himself.

Kahl (p. 247) would have Paul's rhetoric placing us, his late readers, "right back at the foot of the great alar in Pergamon" where she believes, all of his readers are directed by Paul's own deepest concerns - resistance to the empire of the caesars.

Kahl's explication of an "intertextual retelling" (p. 251) helpfully opens Paul's text to creative re-application as anti-imperial in its essence. This is a homiletical gambit.

Kahl and the scholars Kahl cites with approval, as experts in 'intertextual' matters, delineate the indices of the 'intertextual' markers which, coincidentally, have been found in the material they wish to see as relevant. This is like cutting out puzzle pieces and then announcing that one has been successful in putting a puzzle together.

As I have suggested in earlier comments , the context of the material found in Paul's Galatians letter is not illuminated by the linkage Kahl finds between the text of this very specifically focused letter and representational art found at Pergamon.

The constant harkening back to visual art, fashioned decades if not centuries earlier, is warranted neither by what can be surmised from Roman republican and imperial history nor from the circumstances of Paul and his messianic converts in Galatia.

Nor is it illuminating to suggest that what can be called "cryptic" in Galatians is best understood (p. 252) as "a semi-hidden (or semi-public) transcript circulating among the dominated that has an anti-Roman core message."

This is all too forced. Here is an example:

The "single man" of Gal 1:1 is not the emperor in Rome, and so, is not a clue to Paul's intended readers, that "the whole of the following letter needs to be read in an anti-imperial key" (page 257).

Gal 1:1

contains the phrase, 'nor through (a) man' which Kahl takes as a reference to Caesar and from this, concludes (p. 257), that "the law and religion that Paul primarily criticizes are the law and religion not of Judaism but of the Roman empire."

But a perfectly acceptable translation of the verse and therefore of Kahl's cornerstone phrase is:

Paul, an emissary, neither through men nor by a man, but through Messiah Jesus and Father God, who raised him from the dead

Kahl takes "a man" as a cryptic reference to a specific individual, Caesar. This conclusion is stated without addressing a more likely reading.

Paul is asserting that his credentials as a missionary-organizer have been conferred upon him by God. Paul is contradicting his critics, who have asserted that Paul is lacking in qualification and/or proper appointment.

This being the case the reading that suggests itself is that Paul means to contrast positively, his assertion of his own divine commission with a commission or credential dependent, negatively, merely upon human agency. It is not likely that Paul has a specific person in mind.

Even if a specific person is referenced here, as some commentators suggest - someone whom Paul intends to denigrate - the reference is to a leader of the messianists in either Antioch or in Jerusalem.

The human-agency conclusion has been reached by many; ("human channel" Burton, p. 3 [1968]; 'human in origin" Betz, p. 39; "not depend on human authorization" Dunn, p. 26; anthropos = "the human orb" Martyn, p. 84).

Kahl, in proposing an entirely new interpretative direction, i.e., that Paul is here referring however cryptically to Caesar, ought first contend with comments which point, cogently, in another direction - not through any human being.

In sum, Professor Kahl, in chapter six, is engaged in homiletical gambits, not historical investigations.

That's OK with me. "It's right to praise . . . not meaning, but feeling . . . " ("Why I'm Here" by Jacqueline Berger, from The Gift That Arrives Broken. © Autumn House Press, 2010.)

NOTE: The Greek text of Gal 1:1, used above, has been taken from Greek New Testament

Labels:

Brigitte Kahl,

Galatians,

Paul,

Pergamon

Sunday, February 13, 2011

RESPONSE NUMBER TWENTY-SEVEN To Galatians Re-imagined: Reading with the Eyes of the Vanquished (Fortress 2010) by Brigitte Kahl

The sub-title of Chapter Four is emblematic of a double aspect in Kahl's approach to the historical events she is investigating.

That sub-title is, "The Imperial Resurrection of the Dying Gauls / Galatians (189 B.C.E. - 50 C.E.)"

This sub-title conveys two ideas:

(1) a segment of human history is under review;

(2) the writer applies to this review a conceptual matrix, a template of interpretation, through which past events are to be understood.

Imperial, resurrection, dying, all are suggestive symbols; each can resonate emotionally, especially (may I suggest) the latter two.

In combination, it appears to me, these language symbols become code for a perspective on past events, which the writer presses. Nothing wrong with this, of course. But it is good to keep in mind the writer's dual focus, which she is of course straightforward about, beginning with the title of the book. We are to consider past events and re-imagine the import of these events.

Chapter Four has the flavor of a legal brief; it is an argument intended to persuade. The opened-ended title of the chapter, ROMAN GALATIA, indicates neutrality, while the sub-title provides an interpretation. There is room, always (isn't there?) for more than one interpretation.

The strength of Kahl's presentation is its delineation of the startlingly brutal and pervasive methods of the Roman imperium to control occupied peoples. These methods, developed over centuries, sought to create a publicly displayed consensus for and by subjugated peoples, a consensus which affirmed the facts of defeat, occupation and the sustaining principles of world empire.

Prior to chapter four, Kahl grounded her interpretation of events in a detailed examination of visual representations, mostly statues and sculptures.

A literary interpretation of works of art is a translation of visual symbols into an array of written symbols. Although written interpretations of art are commonplace, bear in mind that an explication of a visually perceived set of symbols into a learned set of written symbols does not lend itself to a single, incontestable conceptual result.

There is always going to be room for disagreement about what a visual presentation means, in written form.

An example is Kahl's conclusion that Galatians are represented as mythological giants. I do not think this case has been made, because representations of Gauls (Galatians) and giants appear together. (See post number twenty-three.)

Chapter Four, under discussion here, is not a delineation of visual representations but of literary remains. Nevertheless, in following Kahl's presentation and the argument it presses, the reader is intended to make the assumption that Galatians are represented as giants. Kahl's insistence upon this (see pp. 173, 178-9, 184, 205) is a distraction and does not appear to me to be required or to serve the larger argument, that Paul's Galatians entails a critique of the Roman imperium.

There is much that Kahl has established and that is likely to endure. She persuasively demonstrates (p. 182) that ethnically more uniform north Galatia (the modern day environs of Ankara) and the ethnically more diverse Roman province to the south (designated Galatia by the Romans), were governed according to similar principles. The details of Kahl's presentation helpfully illuminates the background in which Paul propagandized among these occupied populations.

But this reader must register a caveat at the suggestion that the Roman administrative designation of the south Galatia population as Galatian, therefore, came to be a self-identification, "inclusive of all inhabitants" of the southern province. (p. 187, see also 180.)

I think Kahl, if pressed, would retreat slightly from this conclusion, as it is based on the perspective of the occupier, who intended that subjugated peoples "ideally" (p. 187) would trade in their ethnic allegiances and become compliant and quiescent.

Kahl's frequent reference to Gal 3:1 ("You stupid Celts!") suggests that the writer is pressing the all-inclusive Galatians designation so as to make Paul out in his Galatians letter, to be addressing an ethnically diverse audience, who would in their turn, have understood themselves addressed, even if they were not of Celtic origin.

What happened in 189 B.C.E.?

Kahl begins this chapter with a reminder that Manlius Vulso had conducted a punitive campaign of slaughter of Celtic tribes in Anatolia (see p. 66 f.) , which marked the end to Celtic brigandage (if Celtic occupation had been that) and influence in the region.

But Kahl moves from 189 B.C.E. to discuss events of a century later, (89 B.C.E) when Mithridates (Mithradates VI of Pontus and Armenia Minor), a competitor of Rome, then residing in Pergamon, invited prominent locals to a feast, where he slaughtered most the guests. The victims included leading Celtic figures, whom Mithradates believed would side against him and with Rome.

Professor Kahl interprets (p. 172) this event as evidence that the local Celtic tribes, during the past century had "undergone a miraculous metamorphosis" and were no longer viewed as lawless outsiders.

Kahl also suggests (p. 174) that Mithradates' "decapitation" of local Celtic leadership served Roman interests after his defeat by Pompey in 63 B.C.E, by facilitating Roman selection of a single Celt, Deiotarus, as ruler and enforcer of Roman hegemony.

The coercive principles of Roman provincial governance are chillingly arrayed in this book.

Kahl is undoubtedly correct in stating (p. 181) that the pervasive presence of Roman roads "spells out what it means for a region to become a province."

Inscriptions on milestones (p. 181) placed upon the newly established Roman roads, praised the emperor as "holy" (in Latin: augustus = august; in Greek: Sebastos = august). The road along which the milestone was uncovered was proclaimed on the milestone as a holy gift from the emperor, designated Via Sebastos. This suggests similar designations were given to other (all?) Roman roads in this region.

Oddly missing from the book are maps, which certainly would aid the reader to measure distances and appreciate the value of a system of roads to be employed not only for the rapid movement of soldiers but also for the benefit of commerce and communication, generally.

Kahl believes that surviving rosters of military units, unfortunately not reproduced in this book, suggest (p. 185) that impressment into military service entailed the loss of ethnic identity.

But one wonders if too much is being made, by Professor Kahl, about what an individual soldier's enrollment on a clerk's roster might say about that man's status vis a vis the emperor. Kahl thinks the paperwork appears to indicate that the legionnaire is referred to as "f" - and takes this notation to mean "son" of the unit commander.

Kahl believes this designation is a "tangible" indication that the Roman imperium was declaring it had ". . . officially 'fathered' and newly created these men 'out of nothing' shaping them uniformly in the image of empire . . ."

But ". . . documentation was probably not intended to be read outside the unit and many features (such as the marks annotating rosters) remain unclear." (See Roman Military Service: Ideologies of Discipline in the Late Republic and Early Principate, by Sara Elise Phang, Cambridge University Press, 2008 p. 208.)

Kahl is very good in describing the koinon, the provincial council (assembly) composed of wealthy representatives of the occupied population, whose civic duty required the expensive sponsorship of local religious activities and public games.

The koinion functioned as n echo and therefore a cooptation of the ancient Celtic assembly, the drunemeton. The koinon built temples, paid for public feasts and staged blood-soaked events in the arena(s) in the province - all of which were associated with observances of the imperial cult. Kahl states (p. 187) that, at the time of the apostle Paul, at least ten cities in north and south Galatia sponsored events associated with the imperial cult.

Does the plethora of arenas and the ubiquitous staging of bloody entertainments demonstrate that the cult of the emperor was critiqued or countered in Paul's Galatians? Kahl believes so.

"It is important to understand," Kahl writes (p. 188), "the clash with imperial religion and its koinon that was provoked by Paul when his model of worship and koinonia/community turned out to be based on a quite different concept of the one God and the oneness of humanity."

If the Galatians letter reflects a "clash with imperial religion" then one needs to see citations of the letter which establish this association. Kahl does cite the letter, more frequently in this chapter than earlier one. (A subsequent post will visit each of these citations.)

"Rome needed cities" (p. 189).

Kahl helpfully calls attention (pp. 188-191) to the Roman preference for urban centers. This empire was city-based, even to the extent of impoverishing the countryside and starving the rural population, so as to bring food (and force people?) into the cities.

The convening of a koinon is suggestive of the benefits to the occupier of centralization, to say nothing of the military impressment of large numbers of young men, the building of temples and the staging of entertainments and games. All of this indicates that the Roman imperium, through centuries, saw benefits in collecting subjugated peoples into cities, the better to supervise their behavior and keep everything under control.

Not the least of the benefits to the empire was the subsequent redistribution, to military commanders and others, of tracts of land as a reward for services rendered.

Kahl demonstrates the Roman preference for urban life, by drawing on her well honed power of interpretation of visual imagery. Harkening once again to works of art found at the Great Altar at Pergamon, Kahl reminds that Guia, goddess of the earth, presents her cornucopia to the city goddess, Athena. One wants to add, however, as Kahl noted earlier on, that the Great Altar was designed and constructed by Greek sensibilities and workmanship, later taken over by Rome.

The image of empire as an iconic city was embraced by the imperium. As Kahl expresses it (p. 191): ". . . Roma, the worldwide mother city, the unsatiable divine metropolis . . . [was] worshipped alongside the deified Caesar at Ancyra and elsewhere."

In addition to a discovered Roman military roster and the register of donations by members of a Koinon, Kahl calls attention to two other writings, which highlight the nature of the cult of the Emperor.

Portions of an inscription in Ancyra of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti - Acts of the Divine Augustus - have been found. These publicly displayed stone tables, carved in both Latin and Greek suggest the importance placed upon the giving by the divine emperor of good gifts to subjugated peoples - even in faraway Galatia.

For Kahl, the (enforced) generosity of the koinon is intended by occupier and occupied alike as a reflection of the 'good works' of the emperor. The generosity of the emperor, whether implicitly or explicitly, require a reciprocal gift from the koinon. Such gifts, in the expensive form of temple construction, public feasts or elaborate games in the local arena, preserve and enhance the honor of the individual patron. In turn, these sponsored activities invite (require?) reciprocity from the urban masses, which takes the form of gratitude, obedience and praise to the emperor who has made it all possible.

At this point a template of interpretation is proposed by Kahl, whereby the emperor's largesse is characterized as "works of the law" (p. 196), which is suggestive, in turn, to Kahl, of Paul's arguments in his Galatians letter.

The emperor's gifts are entitled, "benefactor/benefaction" which Kahl states, literally means, "doing of good works" (Kahl, p. 196).

Does the association of the emperor's 'good works' make inevitable, or even more plausible the notion pressed by Kahl, that Paul in his Galatians letter (2:16, 3:2-5) is critiquing the generosity of Caesar as "works righteousness" (p. 199)?

Kahl suggests (p. 199) that Paul is advocating and practicing a "faith righteousness" in opposition to "law righteousness." Paul's messianic allegiance, Kahl argues, does not mirror the "honor, benefaction, and patronage of the divine Caesar but the counter-hegemony of a crucified one."

Kahl also suggests that the prevalence of celebratory meals and public spectacles "resonate" in Paul's references in his letter to table fellowship ("community") and "public death spectacles, that is, crucifixion" (p. 199).

Kahl also argues that the title which has come down through church history of Paul as Apostle to "the Gentiles" needs to be re-examined, in light of the reference to Galatian tribes as ethne. This term, Kahl argues, ought not be assumed to mean Gentile - as opposed to Jew.

There is much here that is persuasive in a general sense and much that provokes a re-consideration of established ideas, as to the background against which was dictated Paul's Galatians letter.

But questions persist:

By way of the mechanisms of Roman subjugation, have the Galatian tribes undergone (p. 204) a "stunning metamorphosis . . . from barbarian outlaws to imperial subjects and soldiers . . . "?

Does the imagery examined indicate that "Dying Gauls had become resurrected . . ." (p. 204)?

Kahl herself raises (p. 204) a question which is central to her investigation: Can we say that Paul "aims much more at the normative imperial master images than at perceptions of Jewish Torah?"

It seems plausible to this reader to agree with Kahl (p. 206) that Paul proposes a "dangerous messianic countervision." But this vision, diverging from the imperial imposition of emperor worship, expressed through public display, does not require that the Galatians letter be seen as an explicit counter to the cult of the emperor.

The messianic faith that Paul helped to found and propagate, did reach a kind of counter-position to Rome, but not until the rule of Constantine, and then, more as a cooptation of empire rather than as a counter to empire.

The continuing weakness of Kahl's presentation is a failure to document persuasively what is repeatedly inferred and increasingly asserted as fact, that the coercive, consensus-building methods of the imperium directed at an occupied population, are the subject matter of Paul's Galatians letter. This, the central thesis of Kahl's book, remains unproven.

That sub-title is, "The Imperial Resurrection of the Dying Gauls / Galatians (189 B.C.E. - 50 C.E.)"

This sub-title conveys two ideas:

(1) a segment of human history is under review;

(2) the writer applies to this review a conceptual matrix, a template of interpretation, through which past events are to be understood.

Imperial, resurrection, dying, all are suggestive symbols; each can resonate emotionally, especially (may I suggest) the latter two.

In combination, it appears to me, these language symbols become code for a perspective on past events, which the writer presses. Nothing wrong with this, of course. But it is good to keep in mind the writer's dual focus, which she is of course straightforward about, beginning with the title of the book. We are to consider past events and re-imagine the import of these events.

Chapter Four has the flavor of a legal brief; it is an argument intended to persuade. The opened-ended title of the chapter, ROMAN GALATIA, indicates neutrality, while the sub-title provides an interpretation. There is room, always (isn't there?) for more than one interpretation.

The strength of Kahl's presentation is its delineation of the startlingly brutal and pervasive methods of the Roman imperium to control occupied peoples. These methods, developed over centuries, sought to create a publicly displayed consensus for and by subjugated peoples, a consensus which affirmed the facts of defeat, occupation and the sustaining principles of world empire.

Prior to chapter four, Kahl grounded her interpretation of events in a detailed examination of visual representations, mostly statues and sculptures.

A literary interpretation of works of art is a translation of visual symbols into an array of written symbols. Although written interpretations of art are commonplace, bear in mind that an explication of a visually perceived set of symbols into a learned set of written symbols does not lend itself to a single, incontestable conceptual result.

There is always going to be room for disagreement about what a visual presentation means, in written form.

An example is Kahl's conclusion that Galatians are represented as mythological giants. I do not think this case has been made, because representations of Gauls (Galatians) and giants appear together. (See post number twenty-three.)

Chapter Four, under discussion here, is not a delineation of visual representations but of literary remains. Nevertheless, in following Kahl's presentation and the argument it presses, the reader is intended to make the assumption that Galatians are represented as giants. Kahl's insistence upon this (see pp. 173, 178-9, 184, 205) is a distraction and does not appear to me to be required or to serve the larger argument, that Paul's Galatians entails a critique of the Roman imperium.

There is much that Kahl has established and that is likely to endure. She persuasively demonstrates (p. 182) that ethnically more uniform north Galatia (the modern day environs of Ankara) and the ethnically more diverse Roman province to the south (designated Galatia by the Romans), were governed according to similar principles. The details of Kahl's presentation helpfully illuminates the background in which Paul propagandized among these occupied populations.

But this reader must register a caveat at the suggestion that the Roman administrative designation of the south Galatia population as Galatian, therefore, came to be a self-identification, "inclusive of all inhabitants" of the southern province. (p. 187, see also 180.)

I think Kahl, if pressed, would retreat slightly from this conclusion, as it is based on the perspective of the occupier, who intended that subjugated peoples "ideally" (p. 187) would trade in their ethnic allegiances and become compliant and quiescent.

Kahl's frequent reference to Gal 3:1 ("You stupid Celts!") suggests that the writer is pressing the all-inclusive Galatians designation so as to make Paul out in his Galatians letter, to be addressing an ethnically diverse audience, who would in their turn, have understood themselves addressed, even if they were not of Celtic origin.

What happened in 189 B.C.E.?

Kahl begins this chapter with a reminder that Manlius Vulso had conducted a punitive campaign of slaughter of Celtic tribes in Anatolia (see p. 66 f.) , which marked the end to Celtic brigandage (if Celtic occupation had been that) and influence in the region.

But Kahl moves from 189 B.C.E. to discuss events of a century later, (89 B.C.E) when Mithridates (Mithradates VI of Pontus and Armenia Minor), a competitor of Rome, then residing in Pergamon, invited prominent locals to a feast, where he slaughtered most the guests. The victims included leading Celtic figures, whom Mithradates believed would side against him and with Rome.

Professor Kahl interprets (p. 172) this event as evidence that the local Celtic tribes, during the past century had "undergone a miraculous metamorphosis" and were no longer viewed as lawless outsiders.

Kahl also suggests (p. 174) that Mithradates' "decapitation" of local Celtic leadership served Roman interests after his defeat by Pompey in 63 B.C.E, by facilitating Roman selection of a single Celt, Deiotarus, as ruler and enforcer of Roman hegemony.

The coercive principles of Roman provincial governance are chillingly arrayed in this book.

Kahl is undoubtedly correct in stating (p. 181) that the pervasive presence of Roman roads "spells out what it means for a region to become a province."

Inscriptions on milestones (p. 181) placed upon the newly established Roman roads, praised the emperor as "holy" (in Latin: augustus = august; in Greek: Sebastos = august). The road along which the milestone was uncovered was proclaimed on the milestone as a holy gift from the emperor, designated Via Sebastos. This suggests similar designations were given to other (all?) Roman roads in this region.

Oddly missing from the book are maps, which certainly would aid the reader to measure distances and appreciate the value of a system of roads to be employed not only for the rapid movement of soldiers but also for the benefit of commerce and communication, generally.

Kahl believes that surviving rosters of military units, unfortunately not reproduced in this book, suggest (p. 185) that impressment into military service entailed the loss of ethnic identity.

But one wonders if too much is being made, by Professor Kahl, about what an individual soldier's enrollment on a clerk's roster might say about that man's status vis a vis the emperor. Kahl thinks the paperwork appears to indicate that the legionnaire is referred to as "f" - and takes this notation to mean "son" of the unit commander.

Kahl believes this designation is a "tangible" indication that the Roman imperium was declaring it had ". . . officially 'fathered' and newly created these men 'out of nothing' shaping them uniformly in the image of empire . . ."

But ". . . documentation was probably not intended to be read outside the unit and many features (such as the marks annotating rosters) remain unclear." (See Roman Military Service: Ideologies of Discipline in the Late Republic and Early Principate, by Sara Elise Phang, Cambridge University Press, 2008 p. 208.)

Kahl is very good in describing the koinon, the provincial council (assembly) composed of wealthy representatives of the occupied population, whose civic duty required the expensive sponsorship of local religious activities and public games.

The koinion functioned as n echo and therefore a cooptation of the ancient Celtic assembly, the drunemeton. The koinon built temples, paid for public feasts and staged blood-soaked events in the arena(s) in the province - all of which were associated with observances of the imperial cult. Kahl states (p. 187) that, at the time of the apostle Paul, at least ten cities in north and south Galatia sponsored events associated with the imperial cult.

Does the plethora of arenas and the ubiquitous staging of bloody entertainments demonstrate that the cult of the emperor was critiqued or countered in Paul's Galatians? Kahl believes so.

"It is important to understand," Kahl writes (p. 188), "the clash with imperial religion and its koinon that was provoked by Paul when his model of worship and koinonia/community turned out to be based on a quite different concept of the one God and the oneness of humanity."

If the Galatians letter reflects a "clash with imperial religion" then one needs to see citations of the letter which establish this association. Kahl does cite the letter, more frequently in this chapter than earlier one. (A subsequent post will visit each of these citations.)

"Rome needed cities" (p. 189).

Kahl helpfully calls attention (pp. 188-191) to the Roman preference for urban centers. This empire was city-based, even to the extent of impoverishing the countryside and starving the rural population, so as to bring food (and force people?) into the cities.

The convening of a koinon is suggestive of the benefits to the occupier of centralization, to say nothing of the military impressment of large numbers of young men, the building of temples and the staging of entertainments and games. All of this indicates that the Roman imperium, through centuries, saw benefits in collecting subjugated peoples into cities, the better to supervise their behavior and keep everything under control.

Not the least of the benefits to the empire was the subsequent redistribution, to military commanders and others, of tracts of land as a reward for services rendered.

Kahl demonstrates the Roman preference for urban life, by drawing on her well honed power of interpretation of visual imagery. Harkening once again to works of art found at the Great Altar at Pergamon, Kahl reminds that Guia, goddess of the earth, presents her cornucopia to the city goddess, Athena. One wants to add, however, as Kahl noted earlier on, that the Great Altar was designed and constructed by Greek sensibilities and workmanship, later taken over by Rome.

The image of empire as an iconic city was embraced by the imperium. As Kahl expresses it (p. 191): ". . . Roma, the worldwide mother city, the unsatiable divine metropolis . . . [was] worshipped alongside the deified Caesar at Ancyra and elsewhere."

In addition to a discovered Roman military roster and the register of donations by members of a Koinon, Kahl calls attention to two other writings, which highlight the nature of the cult of the Emperor.

Portions of an inscription in Ancyra of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti - Acts of the Divine Augustus - have been found. These publicly displayed stone tables, carved in both Latin and Greek suggest the importance placed upon the giving by the divine emperor of good gifts to subjugated peoples - even in faraway Galatia.

For Kahl, the (enforced) generosity of the koinon is intended by occupier and occupied alike as a reflection of the 'good works' of the emperor. The generosity of the emperor, whether implicitly or explicitly, require a reciprocal gift from the koinon. Such gifts, in the expensive form of temple construction, public feasts or elaborate games in the local arena, preserve and enhance the honor of the individual patron. In turn, these sponsored activities invite (require?) reciprocity from the urban masses, which takes the form of gratitude, obedience and praise to the emperor who has made it all possible.

At this point a template of interpretation is proposed by Kahl, whereby the emperor's largesse is characterized as "works of the law" (p. 196), which is suggestive, in turn, to Kahl, of Paul's arguments in his Galatians letter.

The emperor's gifts are entitled, "benefactor/benefaction" which Kahl states, literally means, "doing of good works" (Kahl, p. 196).

Does the association of the emperor's 'good works' make inevitable, or even more plausible the notion pressed by Kahl, that Paul in his Galatians letter (2:16, 3:2-5) is critiquing the generosity of Caesar as "works righteousness" (p. 199)?

Kahl suggests (p. 199) that Paul is advocating and practicing a "faith righteousness" in opposition to "law righteousness." Paul's messianic allegiance, Kahl argues, does not mirror the "honor, benefaction, and patronage of the divine Caesar but the counter-hegemony of a crucified one."

Kahl also suggests that the prevalence of celebratory meals and public spectacles "resonate" in Paul's references in his letter to table fellowship ("community") and "public death spectacles, that is, crucifixion" (p. 199).

Kahl also argues that the title which has come down through church history of Paul as Apostle to "the Gentiles" needs to be re-examined, in light of the reference to Galatian tribes as ethne. This term, Kahl argues, ought not be assumed to mean Gentile - as opposed to Jew.

There is much here that is persuasive in a general sense and much that provokes a re-consideration of established ideas, as to the background against which was dictated Paul's Galatians letter.

But questions persist:

By way of the mechanisms of Roman subjugation, have the Galatian tribes undergone (p. 204) a "stunning metamorphosis . . . from barbarian outlaws to imperial subjects and soldiers . . . "?

Does the imagery examined indicate that "Dying Gauls had become resurrected . . ." (p. 204)?

Kahl herself raises (p. 204) a question which is central to her investigation: Can we say that Paul "aims much more at the normative imperial master images than at perceptions of Jewish Torah?"

It seems plausible to this reader to agree with Kahl (p. 206) that Paul proposes a "dangerous messianic countervision." But this vision, diverging from the imperial imposition of emperor worship, expressed through public display, does not require that the Galatians letter be seen as an explicit counter to the cult of the emperor.

The messianic faith that Paul helped to found and propagate, did reach a kind of counter-position to Rome, but not until the rule of Constantine, and then, more as a cooptation of empire rather than as a counter to empire.

The continuing weakness of Kahl's presentation is a failure to document persuasively what is repeatedly inferred and increasingly asserted as fact, that the coercive, consensus-building methods of the imperium directed at an occupied population, are the subject matter of Paul's Galatians letter. This, the central thesis of Kahl's book, remains unproven.

Labels:

Ankara,

Brigitte Kahl,

Dying Gauls,

Galatians,

Giants,

Manlius Vulso,

Mithradates,

Mithridates,

Paul,

Pompey,

Rome

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

RESPONSE NUMBER TWENTY-TWO To Galatians Re-imagined: Reading with the Eyes of the Vanquished (Fortress 2010) by Brigitte Kahl

These comments are addressed to Chapter Two, sub-head: "The Lawlessness of the Dying Trumpeter - and of Paul" (pp. 78-82).

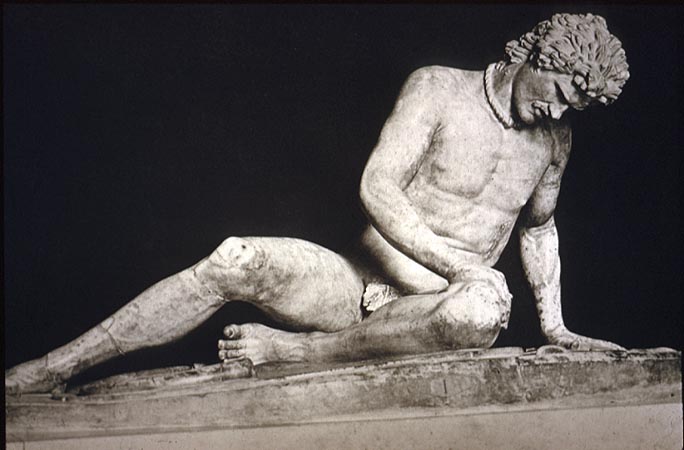

Kahl asserts, that the image of the Dying Trumpeter / Dying Gaul was ubiquitous across the Greek and Roman worlds ("omnipresent images" page 79) and in the first century was understood by means of "a common sigh system of otherness" (p. 78) which "Paul and the Galatians of his letter would "have no difficulty reading" (p. 79).

These assertions lead Kahl to further argue that this sculpture informs not simply the context of Paul's Galatians letter, but the argument(s) contained in the letter. This is so, Kahl states, because of two features of the sculpture: (1) the presentation of an uncircumcised penis and (2) the assailant who has delivered the lethal blow is not pictured.

Conflating the centuries older sculpture with the contemporaneous Galatians of Paul's letter, Kahl allows the imagery of the art to represent the circumstance of Galatians, per se, whose ancestors had been defeated in war. The analogy seems to run in the opposite chronological direction as well: "Is there any relation between his [the statue's] foreskin and the mortal would on his side? And who inflicted the wound? [. . .] Is it Jewish law that has cruelly punished the dying man for not complying with the 'works' of circumcision?"

Kahl expects her reader to see such questions as "bizarre" because, in her view, the tension about circumcision has little or nothing to do with Torah and much to do with the imperious law of the Roman occupiers.

As mentioned in an earlier post, the photographic image below is taken from William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (London: John Murry, 1875) see pp. 574-77.

This sculpture, taken as representing Paul's Galatian converts, means to Kahl (p. 80), "it is not Jewish particularism or ethnocentrism that has struck him [i.e. the Dying Gaul] down but Cesar's imperial universalism."

Are we to impute imperial Roman pretensions to Greek sculpture of an earlier date simply because Rome took possession of these objects?

Even if this question is answered affirmatively, where is there an association between the sculpture and the letter dictated by the Apostle Paul?

One of the problems Kahl faces is that of assigning significance to a work of art, on behalf of an absent set of supposed viewers.

Art engages with individual sensibilities and perceptions which inform each viewer's understanding. Is there a 'correct' way to understand a work of art? Can a particular understanding of a sculpture be assigned with confidence to observers in another time and place?

Art engages with individual sensibilities and perceptions which inform each viewer's understanding. Is there a 'correct' way to understand a work of art? Can a particular understanding of a sculpture be assigned with confidence to observers in another time and place?

A specific historical problem is that much art from the Greek and later Roman eras display an uncircumcised penis. On what grounds is one entitled to announce that any one of these works of art is part of an argument about circumcision?

As mentioned in an earlier post, the surviving marble sculpture of the Dying Gaul / Dying Trumpeter appears, to me, to have been modeled on an even older, strikingly similar bronze figure from the sanctuary of Aphaia, at Aegina, a depiction of Trojan King Laomedon, killed by an arrow from Herakles (Heracles), during the first campaign against Troy. (This image may be found in A History of Ancient Sculpture, Vol 2, by Lucy Mitchell (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1883) p. 244.)

This image also displays a penis. Are we to speculate then that this image, too. is a critique of circumcision? On what grounds, whether historical, esthetic or literary, can this association be made?

In this image, as with the Dying Gaul, the attacker is absent. Dos this mean we are entitled to declare that the attacker is Roman, since imperial Rome later came into possession of Greek art?

Professor Kahl concludes (p. 81) this section by citing an ambiguous comment from Paul (Gal 6:11-13) wherein Paul seems to be saying that those who insist the Galatians must be circumcised, do so "that they may not be persecuted."

Kahl implies that Paul is here referring to "a third party" which Kahl, herself writing ambiguously, takes as "something or someone," of whom Paul's circumcision-insisting adversaries "are genuinely afraid."

Whether a single one of Paul's Galatians ever viewed this sculpture on a single occasion is simply asserted to be true; they all must have seen this statue because it was "omnipresent."

This assertion permits Kahl to speculate that Paul's adversaries might be afraid of the same "invisible hand that struck the deadly blow against the Trumpeter."

This further assertion muddies what is known of the provenance of the sculpture of the Dying Gaul, representing as it does, an adversary defeated in a Greek or Pergamene victory, not a Roman one.

For a new interpretative key to be accepted, displacing a former understanding, the new idea cannot be merely plausible. The new approach must be more plausible than the older approaches. We are not at this point, so far in Kahl's presentation.

In this image, as with the Dying Gaul, the attacker is absent. Dos this mean we are entitled to declare that the attacker is Roman, since imperial Rome later came into possession of Greek art?

Professor Kahl concludes (p. 81) this section by citing an ambiguous comment from Paul (Gal 6:11-13) wherein Paul seems to be saying that those who insist the Galatians must be circumcised, do so "that they may not be persecuted."

Kahl implies that Paul is here referring to "a third party" which Kahl, herself writing ambiguously, takes as "something or someone," of whom Paul's circumcision-insisting adversaries "are genuinely afraid."

Whether a single one of Paul's Galatians ever viewed this sculpture on a single occasion is simply asserted to be true; they all must have seen this statue because it was "omnipresent."

This assertion permits Kahl to speculate that Paul's adversaries might be afraid of the same "invisible hand that struck the deadly blow against the Trumpeter."

This further assertion muddies what is known of the provenance of the sculpture of the Dying Gaul, representing as it does, an adversary defeated in a Greek or Pergamene victory, not a Roman one.

For a new interpretative key to be accepted, displacing a former understanding, the new idea cannot be merely plausible. The new approach must be more plausible than the older approaches. We are not at this point, so far in Kahl's presentation.

Labels:

Aegina,

Aphaia,

Brigitte Kahl,

Dying Celt,

Dying Gaul,

Dying Trumpeter,

Galatians,

Laomedon,

Paul,

Rome,

Troy

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)