CHAPTER TWO – “DYING GAULS / GALATIANS ARE IMMORTAL”

“The Great Alter of Pergamon”

In introductory remarks, Professor Kahl writes (pp. 77-78), “the visual semiotics of dying and dead Galatians is the overall topic of the present chapter” and adds, “Our exploration of the Great Alter [of Pergamon] in both its Pergamene context and in light of its Roman semiotics aims at establishing this unique piece of art as an essential background image, auxiliary context, and intertext for reading Paul’s letter to the Galatians – a ‘complementary system’ for interpreting the text.”

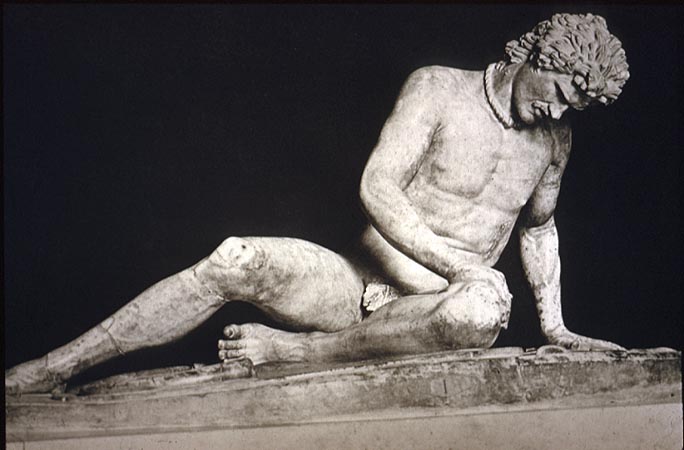

These comments are made in the context of opening up a discussion about the sculpture Kahl identifies as “the Dying Trumpeter,” perhaps better known as “the Dying Gaul.”

The marble sculpture is thought to be a Roman copy of a bronze Greek original commemorating the 230 B.C.E. victory of Attalos over the Gauls. It is to be found today in the Capitoline Museum in Rome.

Photographs of this item are found on page 32 and on the cover. The photographic image below is taken from William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (London: John Murry, 1875) see pp. 574-77.

Earlier scholars have identified the Dying Gaul as a gladiator, but the later consensus is that we are looking at a defeated warrior.

Kahl takes (p. 77) this life size marble figure very sweepingly, to be “a message about sacred violence and the basic order of the world, about victory and civilization: our civilization.”

The marble sculpture of the Dying Gaul / Dying Trumpeter appears, to me, to have been modeled on a centuries older, strikingly similar bronze figure from the sanctuary of Aphaia, at Aegina.

The older work, of a dying warrior, is believed to be the depiction of the treacherous Laomedon, king of Troy, killed by an arrow from Herakles (Heracles), during the first campaign against Troy. This image may be found in A History of Ancient Sculpture, Vol 2, by Lucy Mitchell (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1883) p. 244.

Kahl takes (p. 77) this life size marble figure very sweepingly, to be “a message about sacred violence and the basic order of the world, about victory and civilization: our civilization.”

The marble sculpture of the Dying Gaul / Dying Trumpeter appears, to me, to have been modeled on a centuries older, strikingly similar bronze figure from the sanctuary of Aphaia, at Aegina.

The older work, of a dying warrior, is believed to be the depiction of the treacherous Laomedon, king of Troy, killed by an arrow from Herakles (Heracles), during the first campaign against Troy. This image may be found in A History of Ancient Sculpture, Vol 2, by Lucy Mitchell (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1883) p. 244.

Mitchell catalogues the earlier image as "advanced archaic" and dates it between 500 and 450 B.C.E.

There is no hint of lawlessness in this earlier depiction, apparently of a Trojan warrior or king.

Were the Gauls or Celts ever depicted by the Romans as lawless, i.e., as without law?

So far as I can find, the Gauls / Celts / Galatians were not denegrated as a lawless people. Strabo describes their legal practices in some detail as does Caesar.

There is no hint of lawlessness in this earlier depiction, apparently of a Trojan warrior or king.

Were the Gauls or Celts ever depicted by the Romans as lawless, i.e., as without law?

So far as I can find, the Gauls / Celts / Galatians were not denegrated as a lawless people. Strabo describes their legal practices in some detail as does Caesar.

Is the most plausible suggestion the one that Kahl proposes: that the Gauls / Celts / Galatians were held by imperial Rome to be lawless (pp. 53-4, 61-64, 75) and thus, the representation of them by the Dying Gaul is a depiction of lawlessness?

This seems unlikely to me.

Kahl advances this proposition, it would appear, because Kahl wishes to introduce the idea that Paul in Galatians is "targeting Greco-Roman imperial nomos much more than Jewish Torah," which has been suggested already in the Introduction (p. 7).

Kahl advances this proposition, it would appear, because Kahl wishes to introduce the idea that Paul in Galatians is "targeting Greco-Roman imperial nomos much more than Jewish Torah," which has been suggested already in the Introduction (p. 7).

No comments:

Post a Comment